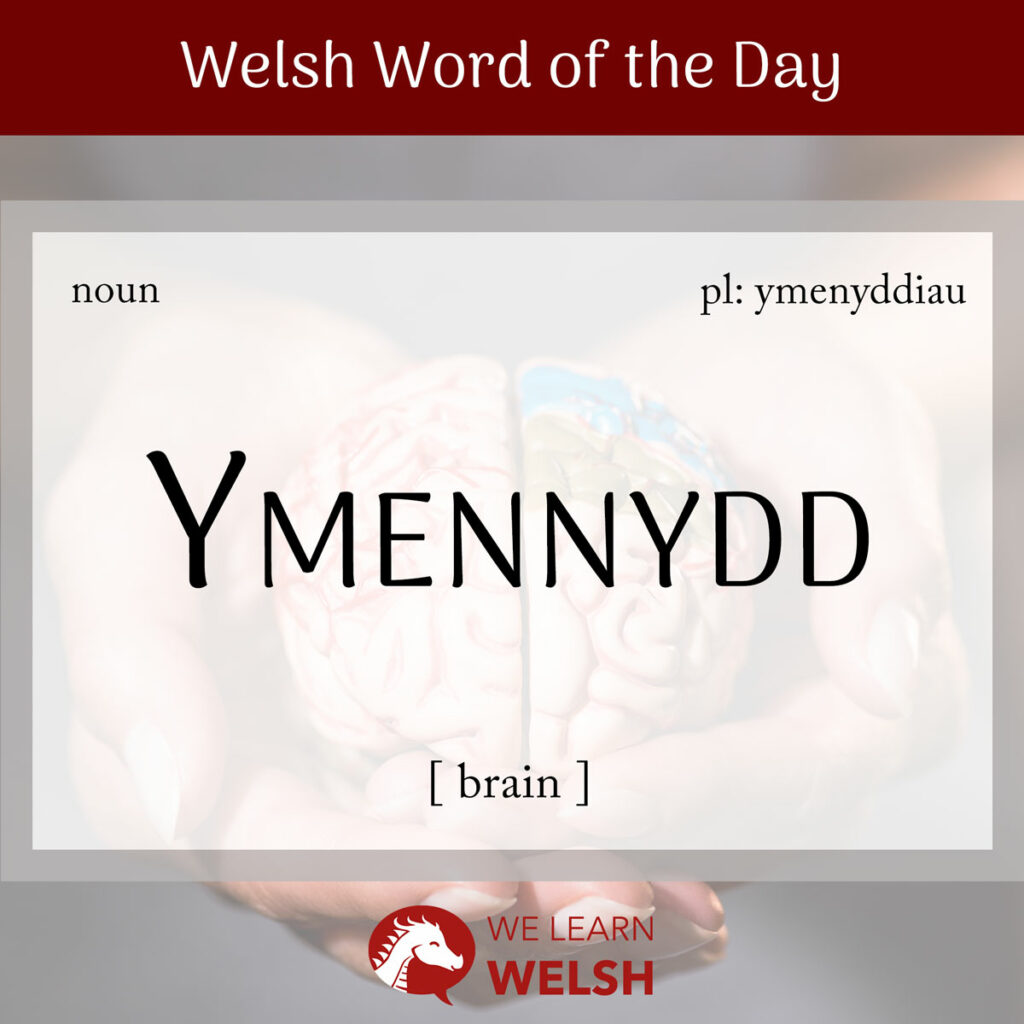

You wouldn’t be darllen (reading) this article without your ymennydd (brain), and I wouldn’t be ysgrifennu (writing) it either. And we certainly wouldn’t be able to engage in dysgu (learning) new languages without our ymenyddiau (brains)!

ymennydd

brain

ymenyddiau

brains

Ymennydd is a masculine noun used in all dialects and registers of Welsh. It comes from the proto-Celtic roots *en, the equivalent of modern Welsh yn (in), and *kwennom, the equivalent of modern Welsh pen (head). Similar constructions exist meaning brain in all of the other five surviving Celtic languages.

Though ymennydd can’t mutate, it can take h-prosthesis, becoming hymennydd. The plural follows the same pattern and becomes hymenyddiau. This occurs – in formal language always, and in colloquial language irregularly depending on the speaker – after eu (their), ein (our), and ei (her), but not after ei (his).

Another thing to be aware of with this noun is that it sounds very like amynedd (patience), so listen out for those subtle vowel differences to avoid getting confused!

Yr ymennydd (the brain) is the organ (organ) that directs the system nerfol (nervous system) of anifeiliaid (animals), including bodau dynol (humans), responsible for processing gwybodaeth (information) and making penderfyniadau (decisions). We usually see yr ymennydd as the physical location of our ymwybod (consciousness) and hunaniaeth (identity).

Within this organ, there are four main areas. The serebrwm / ymennydd uchaf (cerebrum) controls conscious meddwl (thought / thinking), deallusrwydd (intelligence), and cof (memory). The serebelwm / ymennydd bach (cerebellum) controls cydsymud (co-ordination) and cydbwysedd (balance). The hypothalamws (hypothalamus) controls various homeostatic functions, and coesen yr ymennydd (the brainstem, literally the leg of the brain) controls various unconscious or ‘automatic’ functions.

For most people who are neither meddyg (doctor) or niwrowyddonydd (neuroscientist) the most interesting part of yr ymennydd is the serebrwm. This is what’s often referred to in English as the mind, and it’s what makes each unigolyn (individual) themselves.

Mae o’n bwyta cnau i gadw ei ymenydd yn iach ar gyfer ei arholiadau.

He’s eating nuts to keep his brain healthy for his exams.

So what, you may be wondering, is mind in Welsh? There’s not really one straight answer. Instead, if you are translating an English expression using the word mind into Welsh, you’ll need to choose a translation based on context.

Sometimes ymennydd might be right, especially if you’re talking about something more gwyddonol (scientific). Often, the word you’ll be looking for is cof (memory) – for example, the Welsh dal pethau mewn cof (keep things in memory) rather than keep things in mind. Another option is barn, which means opinion and would be relevant if, say, you wanted to say that you and someone else were o’r un farn (of the same mind).

If you are not sure in what direction to go your safest bet is usually meddwl, which works as both a verb meaning to think and a noun meaning thought. It even functions as an adjective sometimes, as in expressions like iechyd meddwl (mental health). To translate the concept of the mind as the seat of ymwybod and hunaniaeth it’s meddwl that you’ll want – but it’s best not to get too used to it as a catch-all, exact translation, because the reality is still a little more complicated.

Actually, meddwl applies to in some cases where we’d say brain in English. Take the expression love on the brain. In Welsh, that’s cariad ar y meddwl.

What if you want to say someone is brainy, as in intelligent? You’ve a whole raft of options, from medrus and galluog (literally able), to the loan word clyfar (clever), to the very complimentary dawnus (gifted / talented). Deallus literally means understanding and is also a good option, and call means intelligent or wise. The closest of all these options to a literal translation of brainy is peniog, which comes from the word pen (head) and simply means clever or intelligent.

This linguistic connection between the pen and the ymennydd continues in phrases like mae ganddi ben da (she’s got brains, literally she’s got a good head) and the less kind does ganddi ddim yn ei phen (she’s got no brains, literally she doesn’t have anything in her head).

Mae ‘mudo ‘mennydd‘ yn broblem ddifrifol i sawl gwlad.

‘Brain drain’ is a serious problem for many countries.

The word ymennydd itself is more likely to come up in terms for disabilities and illnesses. Examples include parlys yr ymennydd (celebral palsy), llid yr ymennydd (brain inflammation) or tiwmor yr ymennydd (a brain tumour).

For more complex medical terms, many Welsh speakers do simply use the English terms as a default. This use of whole English phrases inserted into Welsh speech is very common across multiple contexts. However it’s particularly common in the semantic field of meddygaeth (medicine) simply because most people don’t use these pieces of vocabulary until they’re introduced to them in an ysbyty (hospital) or similar – and English is often the language in which these institutions operate.

Another reason why English terms are sometimes used becomes clear if we look a bit closer at one of the terms I gave earlier, llid yr ymennydd. This literally means inflammation of the brain but it’s very commonly used to mean meningitis. Medically, these are different things, and this is a common phenomenon in Welsh words for clefyd (disease), meaning that sometimes it is better to use the English word for specificity.

So, given the importance of our ymennyddiau, what can we do to keep them iach (healthy)? The short answer is simply to use them as much as possible. Cysgu digon (sleeping enough), bwyd iachus (healthy food), and ymarfer corff (exercise) are all important, but the bottom line is that our ymennyddiau get better at the things they do – meddwl, solving problemau (problems), and processing gwybodaeth – when we give them plenty of opportunities to ymarfer. The good news is that learning a new iaith (language) is one of the best ways of doing this!