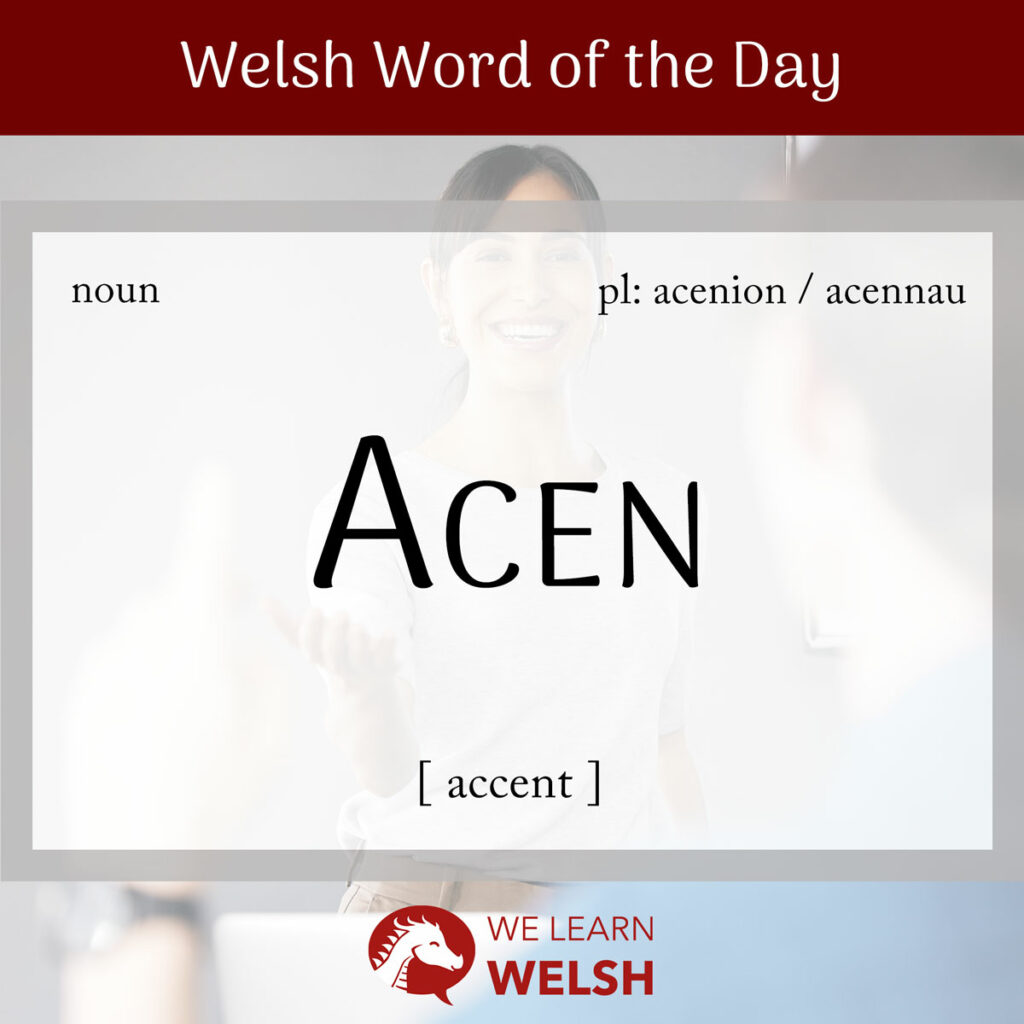

Our Welsh word of the day today is acen (accent). I think it’s a fun one because not only can we dissect it as a word in its own right, but it’s also a good jumping off point for diving into other areas of the Welsh language – like the Welsh acen itself and how it differs throughout the country, and the acenion / acennau (accents), also called diacritics, that are used in written Welsh.

acen

accent

acenion

accents

acennau

accents

Acen is a feminine noun that was borrowed from Lladin (Latin) in the medieval period, probably brought into the language by educated scholars and monks who had exposure to written Lladin. That’s why it sounds so much like the English word accent, and words in the romance languages, like the Italian accento.

I gave two possible plurals above. Acenion is possibly more ‘correct’ and more common in written Welsh, but acennau is fine to use and will sound normal and natural in any conversation.

An acen can refer to quite a wide variety of different things – the term is used in cerddoriaeth (music), cyfrifiadureg (computing), and just generally to describe pwyslais (emphasis).

It shouldn’t get too confusing as you can follow the basic rule that pretty much anything you would call an accent in English can be called an acen in Welsh. As long as you remember to pronounce it with the hard Welsh c, you’ll be grand!

Which leaves us free to focus in this article on the two kinds of acen most relevant to learning a language.

Firstly, an acen is a way of ynganu (pronouncing) a iaith (language) specific to an ardal (region) or group of siaradwyr (speakers).

In Welsh it has one synonym, rarely used and slightly pejorative, which is llediaith. This could describe someone speaking y Gymraeg (Welsh) with an English acen, for example, though most Welsh siaradwyr are very keen to encourage learners rather than tear them down.

Most British people (and perhaps some from further afield!) can recognise when someone is speaking English with a Welsh acen, from the distinctive rolled r sounds and slightly melodic intonation. A lot of people say yr acen Gymreig (the Welsh accent) sounds particularly cyfeillgar (friendly) – if you watched the last series of The Traitors you might have been amused by cystadleuadwr (contestant) Charlotte putting on an acen Gymreig to win people’s ymddiried (trust).

Canwch y nodyn ‘na’n uwch – chi’n gweld yr acen?

Play that note louder – see the accent?

But of course the acen varies within the country as well. Realistically, what most non-Welsh people mean when they say yr acen Gymreig is what they’ve heard on Gavin and Stacey!

To my ear acen y Gogledd (the North Walian accent) sounds much more like someone from Lerpwl (Liverpool) than it does Stacey’s bright Barry acen, or acen y cymoedd (the Valleys accent, which is different again and is also one of the most distinctive South Walian acenion). In fact my English friends often laugh at me when I excitedly declare “They’re Welsh!” on hearing a Scouse person speak on the teledu (television)…

Stereotypically acen y Gogledd is explained as being harsher, though this is quite a negative characterisation which I don’t personally think is fair. It’s just slightly more trwynol (nasal), and less sing-song-y than acenion you’ll hear in South Wales.

When speaking in y Gymraeg (Welsh), North Walian acenion are also characterised by the addition of a whole new vowel sound, the u, which in South Wales is pronounced identically to i.

Plus, vowels remain consistently shorter in the North – in words like tad (dad) or cath (cat) for example, which in standard Welsh have a short a, may be pronounced with a long a similar to â in parts of the South.

Dw i’n dwlu ar eich acen. O ble ydych chi?

I love your accent. Whereabouts are you from?

It’s of course more cymhleth (complicated) than Gogledd a De (North and South) though. What a lot of discourse on Welsh tafodiaeth (spoken language, dialect) fails to account for is that there are so many sub-acenion and sub-tafodieithoedd within both Gogledd a De, and that parts of mid-Wales, like seaside Ceredigion or my home Radnorshire, have their own unique patterns of siarad (speech).

Plus, the complexity of the gwahaniaethau (differences) between Gogledd a De can I think sometimes be scare-mongered a bit to new dysgwyr (learners).

There are certainly those gwahaniaethau, but there are different acenion throughout Lloegr (England), too, and pretty much every other gwlad (country) in the world. And although it’s undeniable that the vocabulary shifts from one end of Cymru (Wales) to the other, you are very likely to be understood in Gogledd Cymru (North Wales) speaking a more Southern variety of the language, and vice versa. It’s you who may have some trouble understanding other people at first!

At the end of the day, part of the fun of learning y Gymraeg is getting more confident clywed (hearing) and deall (understanding) all these very different acenion – and seeing the beauty in all of them.

The second sense of the word is to describe diacritics, which are an arwydd (sign) that is used to mark a difference in ynganiad (pronunciation), tôn (tone), or pwyslais (emphasis) on a particular llythyren (letter) in a gair (word).

Occasionally you may hear or see the phrase nod acen / accenod (accent note) used in order to engender greater specificity, but generally there is no separate word for specifically a diacritic in Welsh; you should just say acen. Trying to Welsh-ify diacritic or employ it as a loan word isn’t something I’d personally recommend just because it isn’t the most commonly known gair even in English!

Acenion of this kind are used in many ieithoedd, particularly those with gwyddorau (alphabets) – English is actually quite unique in its comparative rejection of them.

Dw i ‘di methu fy mhrawf Ffrangeg oherwydd anghofiais yr acenion!

I’ve failed my French test because I forgot the accents!

Y Gymraeg is much more sensible, and makes use of four acenion. These are the acen lem / acen ddyrchafedig / acen fer (acute accent), acen leddf / acen ddisgynedig (grave accent), to bach / acen grom / hirnod (circumflex) and didolnod (diaeresis).

The acen lem and acen leddf are sometimes omitted in writing, so don’t let them keep you up at night, but it’s useful to know what they mean and how they’re used.

The acen lem is for showing that pwyslais in a particular gair is on a different sillaf (syllable) to what we’d expect.

For instance, take the word sigarét (cigarette). The normal Welsh pattern of ynganu would have us pwysleisio (emphasise) the middle sillaf, which is gar. However, we actually pwysleisio the last sillaf, probably because it’s a loan word and we’re imitating the English and French ynganiad. The acen lem makes that clear in writing.

Just to make things more confusing, this rule isn’t universal. Take the word Cymraeg (Welsh) itself; although the emphasis is on the final syllable, it’s not written with an acen lem.

The acen leddf also often shows up in loan words – though also not exclusively. What it does is suggest that a llafariad (vowel) we might have expected to be long should actually be short.

This can differentiate words, like mwg (smoke), pronounced with a longer w, and mẁg (mug), with a shorter one.

Y to bach sy’n dynodi’r gwahaniaeth rhwng ‘tân’ a ‘tan‘.

The circumflex denotes the difference between ‘tân’ and ‘tan‘.

The didolnod (diaeresis) is also sometimes ignored, though probably less frequently than the acen lem and acen leddf. Its purpose is to show that two llafariadau next to each other should be pronounced as two sillafau rather than blended into one sound. It comes up quite a lot in verbs, like copïo (to copy). The didolnod shows we should say cop–i–o, not cop–io.

Lastly and most importantly, there is the to bach (circumflex, literally little roof). The to bach has a simple purpose and is never omitted in correct written Welsh.

Basically, it shows that a llafariad is long. It’s really important to include because compared to the other acenion it’s much more often used to differentiate two geiriau (words) that would otherwise be identical – tân (fire) and tan (until), môr (sea) and mor (so / as), bûm (a conjugation of bod, to be) and bum (a mutation of pum(p), five)are just the beginning of it. I could go on and on!

So don’t stress over Welsh acenion – either kind. But do take the time to get to know the to bach on your learning journey… it’ll serve you well.