There are plenty of Welsh words that have more than one form. Sometimes, the form you’ll hear used is based on region, sometimes formality, and sometimes there doesn’t seem to be much rhyme or reason to it beyond family tradition and personal preference.

One example of this is the word wyneb or gwyneb, meaning face. I’ll go into why these two versions exist in a second, but for now – our Welsh word of the day is the masculine noun wyneb. The plural of wyneb is wynebau (faces).

wyneb

face

wynebau

faces

I should also quickly note that there are pronunciation differences for this word regionally. Some South Walians pronounce it like this:

And in North Wales, colloquially, you may hear this:

Wyneb comes from the proto-Brittonic *eneb, itself from the proto-Celtic *enikwom – and these root words mean exactly the same thing too, which is face. In fact, in Breton and Cornish, the modern forms of the word are much more similar to the original, being eneb and enep respectively. The words in the modern Gaelic languages come from a separate root, but there was a word enech for face in Old Irish.

So what about gwyneb? Where does that fit in?

The answer is fascinating. You may know that in Welsh, words beginning with a g lose that initial letter when they undergo soft mutation. This has resulted in a phenomenon by which many words that begin with a vowel have gone through a process of ‘back-formation’, which means that Welsh speakers began to write and pronounce them with a g at the beginning, as if the original form was actually a soft mutation.

This is what happened to wyneb. Somewhere along the line there was an assumption that wyneb must be a mutated form of an original word gwyneb, and therefore gwyneb developed. The same thing has happened to words like iâr (chicken) and allt (hillside), becoming giâr and gallt respectively.

What does this mean for a learner? Well, the default form of the word is wyneb, and one bonus of this form is that you don’t have to learn any mutations for it either. But if the people you speak to in Welsh most often go for gwyneb, you’ll probably end up picking that up instead – and that’s absolutely fine too. It is now considered a correct, acceptable variant of wyneb, which has developed through natural evolution in the language.

If you do use gwyneb, you’ll need to be aware of its mutation pattern, which is:

Soft mutation

wyneb

Nasal mutation

ngwyneb

Aspirate mutation

N/A

Meaning you’ll end up saying wyneb some of the time anyway!

So if you’ve ever wondered why some people say dy wyneb (your face), fy ngwyneb (my face), and eich gwyneb (your face, formal or when addressing a group), and others simply say dy wyneb (your face), fy wyneb (my face), and eich wyneb (your face, formal or when addressing a group), this is why. It’s not a mutation error, it’s just a different form of the word.

Another complicating factor is h-prosthesis. You may know that the word ei in Welsh can mean his or her. But there’s also an interesting rule where words that start with a vowel should have an h added to the beginning after ei when it means her.

That would mean that his face is always ei wyneb, but her face should technically be either ei gwyneb or ei hwyneb depending on whether you are using gwyneb or wyneb as your base word.

However, many people do omit h-prosthesis when speaking informal, colloquial Welsh – so some of the wyneb gang will simply say ei wyneb.

Mae fy wyneb yn teimlo’n seimllyd iawn heddiw.

My face feels really greasy today.

Ultimately, you can see gwyneb as kind of an etymological descendant of wyneb, but just one that happens to mean the same thing. It certainly has many siblings:

- wynebu = to face

- arwyneb = a surface

- dauwynebog = two-faced

- wynebol = beautiful, honourable (literary)

- wynebgaled = impudent

- wynebwerth = face value

There’s even a couple more variants of the root word itself. These are wynepryd, which is a very formal and literary term, and on the other end of the spectrum, the slang word gwep.

A lot of these words reveal something important about wyneb, which is that like its English equivalent, it doesn’t just refer to the physical wyneb of the pen (head) that we have on our corff (body).

It can also refer to the face, front, or surface of an inanimate object, like the wyneb (front / façade) of an adeilad (building), wyneb y ddaear (the surface of the earth), or, in its verbal form, ffenestr sy’n wynebu’r haul (a window that faces the sun). Speaking of yr haul (the sun), there is a lovely Welsh phrase yn wyneb yr haul (in direct sunlight, literally in the face of the sun).

Because it’s to do with the wynebau (surfaces) of pethau (things), wyneb is the word to use when those wynebau are the wrong way round in someway! In Welsh there are a huge variety of ways to say upside-down, like the very pragmatic pen i lawr (head to the down) or traed i fyny (feet to the up), but wyneb i waered (face to the bottom) is one that’s particularly common.

In a similar vein we have tu wyneb allan (inside out, literally face side out), though again there are other possibilities too, like tu chwith allan (left side out) and the simple tu mewn tu allan (inside outside).

Mae deilen yn arnofio ar wyneb y dŵr.

There is a leaf floating on the surface of the water.

Wyneb even applies to abstract concepts. Take the phrases yn wyneb perygl (in the face of danger) and yn wyneb y gyfraith (in the face of the law) for example. At times in your life you might be forced to wynebu’r gosb (face the music, literally face the punishment), which uses the verb wynebu rather than the noun.

Another one is putting a brave face on it, which in Welsh is wynebu anffawd orau y gallwch (facing misfortune as best you can), or sometimes, among older North Walians, dal blawd wyneb.

This latter comes from the idiom blawdwyneb (flour-faced) which refers to either superficial, flattering and hypocritical respect / approval, or to someone who is viewed in such a way, combined with the idiom dal wyneb (holding face), which usually means pretending to like someone.

You can also arbed wyneb / safio wyneb (save face) and colli wyneb (lose face) just like in English.

Another interesting usage of this word in Welsh – one which actually does differ slightly from English – is to talk about someone being cheeky or rude.

The term wynebgaled (impudent) that I mentioned before is an example of this, but it goes even further. Where you might say that’s enough cheek in English, in Welsh you would say digon o wyneb (enough face). Similarly, you could say am wyneb! (what a face!) for what cheek!

These phrases will be recognised throughout Wales, but overall they are more common in the North. In the South, you could choose between using the wyneb option and the alternative ewn, an adjective that means confident or shameless. If you were visiting your mam-gu (Southern word for granny) and you said you weren’t a big fan of her new llenni (curtains), she might respond dyna ewn! (that’s cheeky!)

All these non-literal possibilities aside, we have to acknowledge that it is pretty important to be able to use the word wyneb to talk about, well, eich wyneb (your face / one’s face).

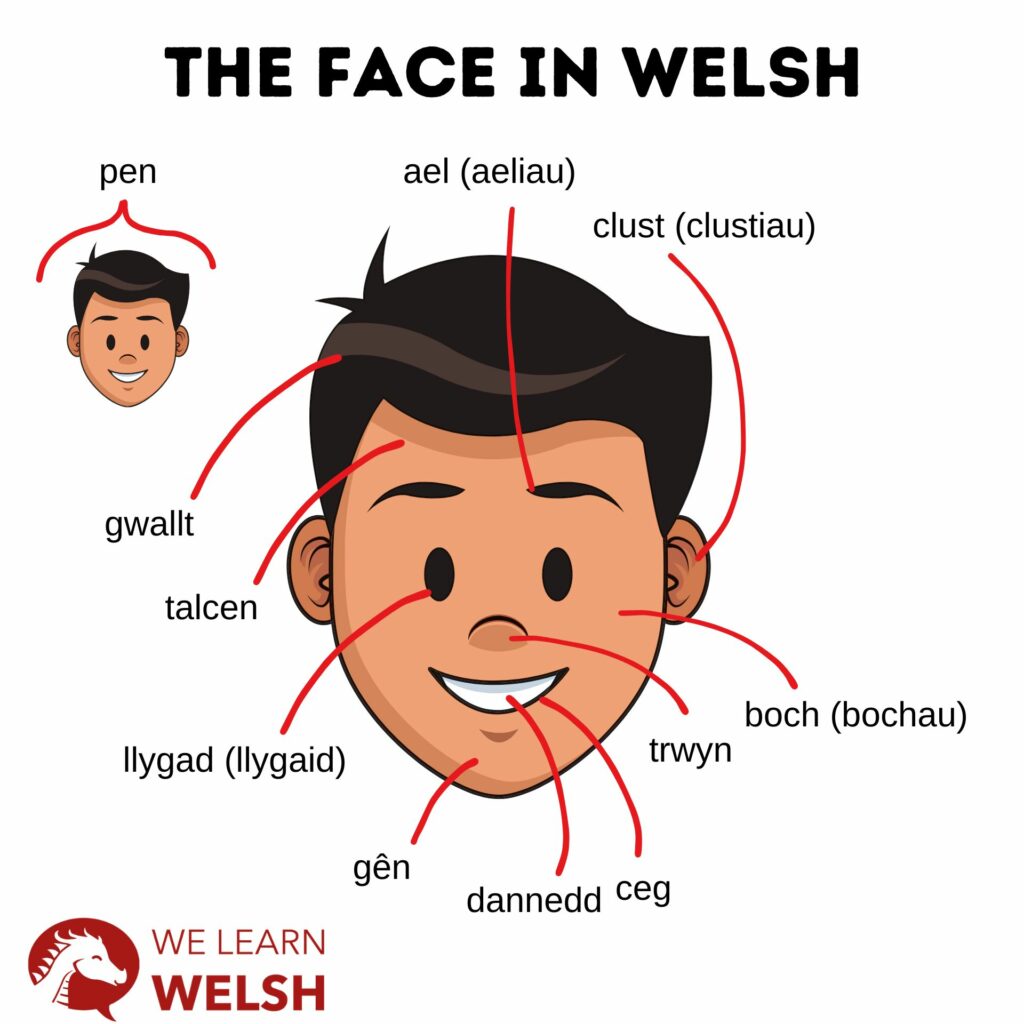

There is a commonly sung Welsh translation of Head, Shoulders, Knees and Toes which teaches us the words for some of the most important facial features:

Pen, ysgwyddau, coesau, traed (coesau, traed)

Pen, ysgwyddau, coesau, traed (coesau, traed)

A llygaid, clustiau, trwyn a cheg

Pen, ysgwyddau, coesau, traed (coesau, traed)

Head, shoulders, knees, and toes (knees and toes)

Head, shoulders, knees, and toes (knees and toes)

And eyes and ears and nose and mouth

Head, shoulders, knees, and toes (knees and toes)

As you can see, the Welsh version often drops the a (and) because there aren’t enough syllables. I’ve left that as it is, but I have reversed mouth and nose in the English version into nose and mouth to match the Welsh, just so that you don’t get trwyn (nose) and ceg (mouth) mixed up.

Another confusing thing is that in this rhyme, ceg appears in the mutated form cheg! This is because the word a (and) causes an aspirate mutation. Ceg is the default.

Aside from these you might also want to know:

- penglog = skull

- talcen = forehead

- aeliau = eyebrows

- blew amrant / blew llygaid = eyelashes

- bochau = cheeks

- dannedd = teeth

- gwefusau = lips

- clustiau = ears

- gên = chin

- gwddf = neck

And there are plenty of ways to describe the kind of gwyneb someone has or is making, too.

Gwenais yn llydan ac yn onest pan welais ei wyneb.

I smiled broadly and honestly when I saw his face.

For example, someone who looks ifanc (young) has wyneb babi (a baby face).

And someone who is trying to keep a straight face is cadw wyneb (keep face).

Someone who looks trist (sad) has wyneb hir (a long face), or traditionally in some parts of the North-West wyneb fel mis pump (a face like month five). Plus you can translate the English expression her face fell literally – wnaeth ei wyneb syrthio.

You can also say gwneud gwep (doing a face), which can refer to someone pulling a sad, annoyed, or disgusted face. If you’re talking about pulling funny faces to make someone chwerthin (laugh), you could also use gwneud gwep, especially in the South, but many people would instead use the simple tynnu wyneb (literally pulling a face).

But there are countless dialectical options for this also, from gwneud ceg hyll (doing an ugly mouth) to gwneud migmars (a very silly, casual way of saying doing sorcery), gwneud siapse (doing shapes) to gwneud ystumiau (doing gestures), and gwneud tursiau (doing grimaces) to gwneud cwpse (a silly Southern word the proper meaning of which I’m not sure of!)

And we do also use wyneb, as in English, to refer to doing something in person or directly. The go-to expression for most people would be wyneb yn wyneb (face-to-face, literally face in face). If you said something to someone’s face, you did so yn ei wyneb (in his face / in her face).

Phew! That was a lot to cover. Can you think of any uses of wyneb that I didn’t get to?