Have you ever wished you had adenydd (wings)? It’s a common theme throughout human history, from the story of Icarus and his balchder (pride) to the Wright brothers who eventually pioneered modern awyrennau (aeroplanes).

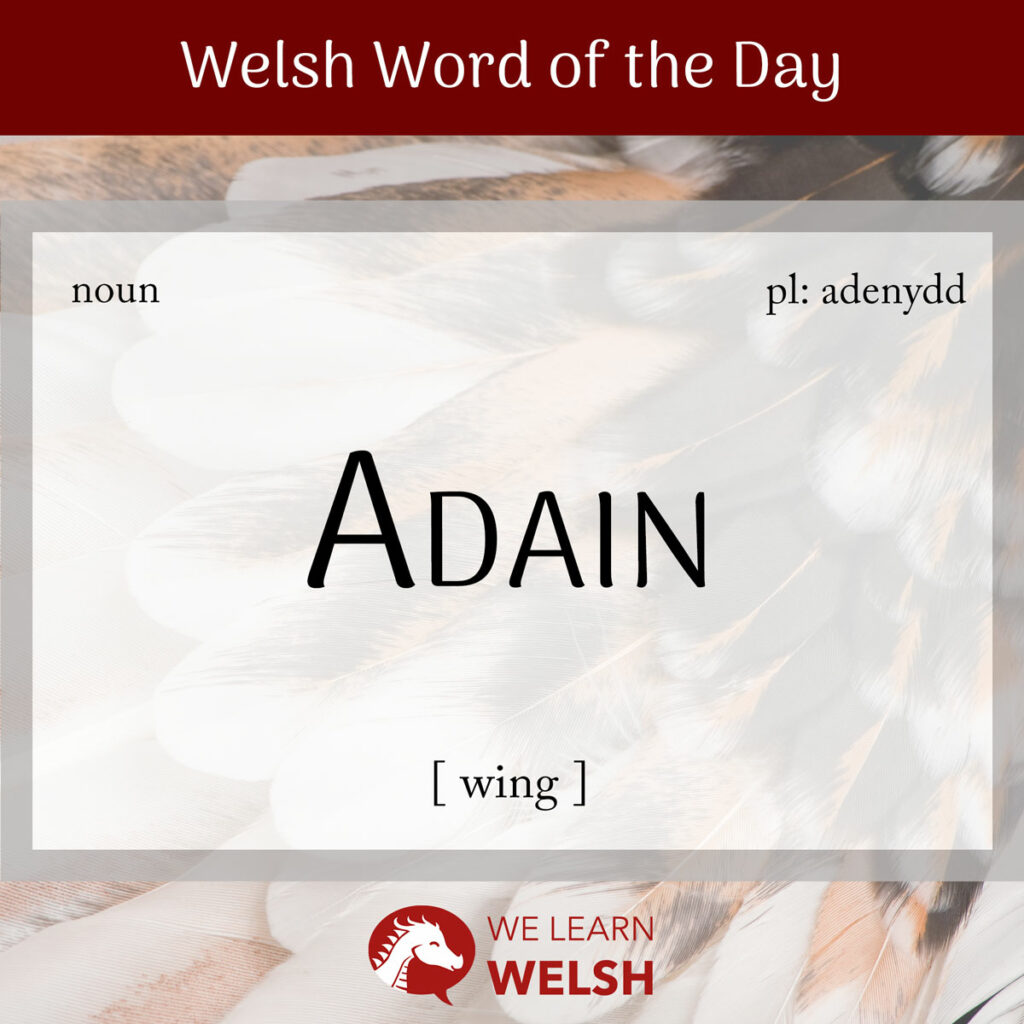

There are two forms of wing in Welsh. One is adain and the other is aden. Most often, although not exclusively, you will see it written adain but pronounced adan or adan. This is because aden is more modern and informal.

adain

wing

adenydd

wings

These words come from the proto-Brittonic root *atani, which is also the source of the words aderyn (bird) and hedfan (to fly). And *atani itself is almost certainly derived from *pet(h), a root in proto-Indo-European thought to have meant to spread wings.

It’s quite useful for memory that aderyn and adain are so similar, although one important difference is that aderyn is masculine while adain is feminine. Luckily both words are very often used in the plural, where grammatical gender is rendered unimportant.

The plural of adain is another source of problems though. Most people say adenydd and this is what you will find in, for example, modern science textbooks. But it can be pronounced more like adanydd, adeinydd, or adenedd in various parts of the country.

Gurodd y ddraig ei hadenydd enfawr.

The dragon flapped its huge wings.

Plus, in poetry you might come across archaic literary plurals such as edyn.

Be it in adar or peiriannau (machines), ehediad (flight) is made possible by simple gwyddoniaeth (science). The adain interacts with the awyr (air), manufacturing an upward grym (force). In adar, energy for the maintenance of forward motion is created by curo adenydd (flapping / beating wings), whereas humans replicate this in our peiriannau with an injan (engine).

Though adar aren’t the only adeiniog (winged) creature in the animal kingdom: let me also pay my respects to ystlumod (bats) as well as many kinds of pryfed (insects), like gwenyn (bees), mosgitos (mosquitoes), and pili-palod (butterflies).

While the adenydd of adar are pluog (feathery), in pryfed they are constructed of a thin pilen (membrane) strengthened by gwythiennau (veins).

And there’s one kind of adain that’s made out of something completely different – that’s adain olwyn, the spoke of a wheel. Sometimes this is called braich olwyn (literally arm of a wheel) instead, or just sbocsen.

Mae o’n bwriadu creu adain fecanyddol.

He means to create a mechanical wing.

In Welsh, adenydd and esgyll (fins) are closely linked to each other. Some people use the word asgell (a fin) for an adain, and the very fun pysgadain (fishwing) is an alternative to asgell too.

Plus, esgyll and asgell are used in a lot of less literal phrases that would use wing in English. One example would be the wing of a political plaid (party); another is in pêl-droed (football), where a wing player is an asgellwr. To wait in the wings is to disgwyl yn yr esgyll, and once you finally get out onto the stage you are lledu’ch esgyll (stretching your / one’s wings).

As in English, you can cymryd rhywun dan eich adein (take someone under your wing), or, on the other end of the spectrum, you can torri adenydd rhywun (clip someone’s wings) to stop them from cael gwynt o dan ei adain / cael gwynt o dan ei hadain (getting wind under his wings / getting wind under her wings). Not as pleasant!

One that’s more unique to Welsh is naill adain. This poignant saying from South Wales means one-winged, and is used to describe someone who has lost a spouse.