Many people see snakes as a symbol of evil or danger, an image that traces its origin all the way back to the Bible, with the demon that tempted Eve often represented as a snake. In more modern popular culture, the snake is the chosen pet of Voldemort in the Harry Potter series.

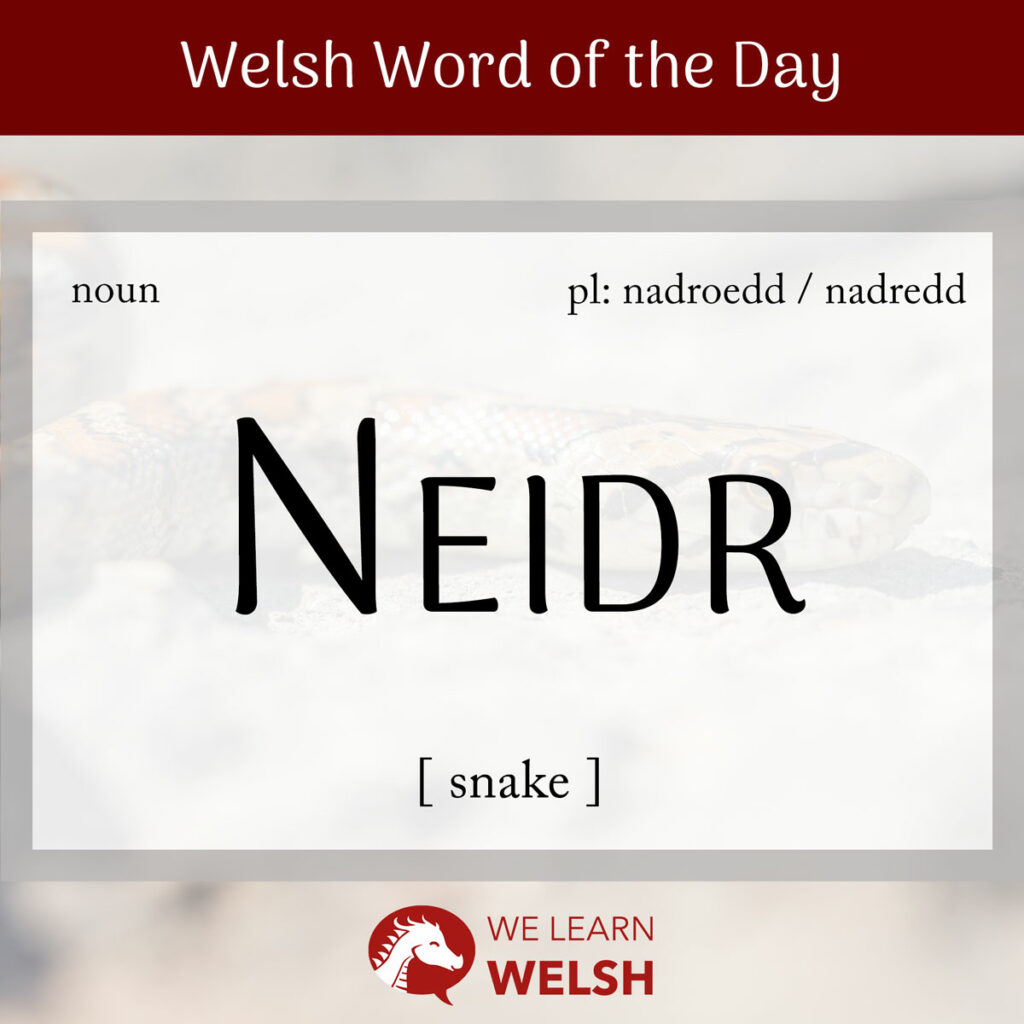

The Welsh word for snake is the feminine noun neidr, and the plural is nadroedd or sometimes nadredd.

neidr

snake

Neidr probably comes from the proto-Celtic *natrixs, and there are similar words in the other Celtic languages, like nathair in Irish and Scottish Gaelic and naer in Breton. In Old English, too, the most common word for snake was the cognate næddre. Ultimately, all these words come from the proto-Indo-European root *sneh, meaning spin or twist, which is also the ancestor of the Welsh words nodwydd (needle) and noden (thread).

Neidr is the most common word for snake, but in the South-East, you may occasionally hear nadredden, which has been formed ‘backwards’ from the plural form nadredd. There is also the word sarff, which is literary and more accurately translated as serpent. Geiriadur Prifysgol Cymru also lists neidryn as a diminutive form for a young snake, although I don’t think baby snakes are something that come up much in everyday conversation!

Unfortunately for snakes, the adjectives we most often used to describe them aren’t always the nicest. Here are some common examples:

- ymlusgol = creeping

- llysnafeddog = slimy

- gwenwynig = venomous

- dychrynllyd = scary

- arswydus = frightful

- ych-a-fi = disgusting

- ymlithrol = slithering

- sinistr = sinister

Over and above all of these, my favourite word to describe snakes might be the verb sleidro, a Southern slang word for to slither or to slide.

Mae’r neidr yn sleidro yn yr isdyfiant.

The snake is slithering in the undergrowth.

Nadroedd are ysglyfaethwyr (predators) which prey on a variety of small creatures, including madfallod (lizards), llyffaint (frogs), llygod (mice), pysgod (fish), and adar (birds). They are ymlusgiaid (reptiles), meaning they begin their life cycle as wyau (eggs) and that they are â gwaed oer (cold-blooded).

Nadroedd are also one of the few reptiles that are heb aelodau (limbless), and their bodies are long and hyblyg (flexible) with wriggling cynffonau (tails). They are known for their sharp dannedd (fangs), and many snakes immobilise or kill their ysglyfaeth (prey) by injecting them with gwenwyn (venom) through a brath neidr (snakebite), although some instead kill by gwasgu (constricting).

Around one-third of adults report experiencing ofn nadroedd (a fear of snakes), although for only around 3% of the population can this be considered genuinely diagnosable. Still, it would probably gyrru ias i lawr ei cefn (send a shiver down his/her spine) for most people to have to visit somewhere nadreddog (snake-infested).

Mae nadroedd yn codi arswyd arnaf.

Snakes really frighten me.

There are plenty of different species of snakes, from Britain’s only venomous snake, the gwiber (adder), to the terrifying march-gobra (king cobra). Below is a handy guide to the Welsh words for some of the most famous kinds of nadroedd:

- neidr ardysog = garter snake

- neidr ddolennog = sidewinder

- neidr y dŵr = water snake or eel

- peithon = python

- neidr ruglo = rattlesnake

- neidr wasgu = boa constrictor

- neidr ddefaid = slowworm

- gwiber / neidr ddu = viper

- môr-neidr / neidr fôr = sea snake

- neidr fraith / neidr lwyd = grass snake or ringed snake

The term neidr can also refer to unrelated species, from plants such as the blodyn neidr (red campion, literally snake’s flower) and tafod y neidr (adder-tongue fern, literally snake’s tongue), to insects like the neidr gantroed (centipede, literally hundred-foot snake) and the beautiful cannwyll neidr or gwas y neidr (dragonfly, literally snake’s candle or snake’s servant). This stems from an old British folk legend that dragonflies would follow snakes to heal their wounds.

I’ll leave you with a wise Welsh idiom: “Anodd i neidr anghofio sut i frathu”. This means “It’s hard for a snake to forget how to bite”, and is the equivalent of the English “A leopard doesn’t change its spots”.